By Sophie Cianfarani, Appraisal Intern, Appraisal Bureau

Art historians hold varied views on the origins of digital art. Roboticists might trace its inception to antiquity, viewing early robots as digital art’s forebears. Some locate digital art’s origin in the 19th century with the jacquard loom’s punch card system, an automated system of control that greatly influenced early computer development. In this exploration, I begin with the mid-20th century––an era distinguished by funding for technological advancements because of the Second World War.

World War II resulted in technological developments and catalyzed discourses around Information Theory, Artificial Intelligence, Communication Theory, and Systems Theory (Charlie Gere, “Cybernetic Era,” in Digital Culture). Cybernetics, derived from the Greek word "kybernētēs," meaning steersman, was a term coined by mathematician Norbert Wiener in the mid-1940s. Cybernetics is the science of control and communication. Cybernetics considers communication as a system in which a living being or machine imparts a message onto another living being or machine, which returns a message related to the input, or original message (Norbert Wiener, “Cybernet`ics in History”). The cybernetic framework laid the foundation for responsive, reactive art that responds to its environment.

Nicholas Schöffer’s Cybernetic Tower, St. Cloud, 1955 is an early example of an artist’s embrace of cybernetics. This tower produced various colored lights and musical sounds based on environmental data such as wind, noise and light levels, and humidity. The tower’s musical compositions and light displays on color projectors were all influenced by environmental conditions. Unlike mechanical devices, where the range of possible outcomes is predetermined, the feedback of cybernetic machines depends on the machine’s environment, making the work more responsive. Artist Roy Ascott, in his book Telematic Embrace: Visionary Theories of Art, Technology, and Consciousness, recognized that modern art, even without directly creating cybernetic systems, embodies the essence of cybernetics by embracing the unpredictable nature of outcomes.

“La Tour Spatiodynamique et Cybernétique at the first Salon International des Travaux Publics et du Bâtiment at Parc du Domaine de Saint-Cloud near Paris, 1955.” image retrieved from ARPA Journal, https://arpajournal.net/towards-dematerialization/

Kenneth Knowlton and Leon Harmon, two engineers at Bell Laboratories with access to new technologies, created a series of images in 1966 called Studies in Perception. Computer Nude was an image within this series that began with a photo negative of the choreographer Deborah Hay. The negative was scanned using BEFLIX (a computer animation language created by Knowlton), converting the image into a series of small pixels with varying gray levels (Zabet Paterson, Peripheral Vision: Bell Labs, the S-C 4020, and the Origins of Computer Art). From up close, the work is only pixels, from afar the image could be taken in as a whole, thus depending on the viewer to investigate different forms of the work by changing their position.

Leon Harmon and Ken Knowlton, Computer Nude (Studies in Perception I), 1967, image retrieved from Buffalo AKG Museum, https://buffaloakg.org/artworks/p20142-computer-nude-studies-perception-i.

Harold Cohen’s 1973 work, AARON, is a computer program that uses artificial intelligence to perpetually generate new creations. AARON is considered a collaborative tool for human-made art, as it was designed with the purpose of exploring the formal elements of drawing and painting. Programmed in 1973, AARON continues to produce new works, reaching no final form.

AARON, Untitled drawing detail, ca. 1980, image retrieved from Computer History https://computerhistory.org/blog/harold-cohen-and-aaron-a-40-year-collaboration/.

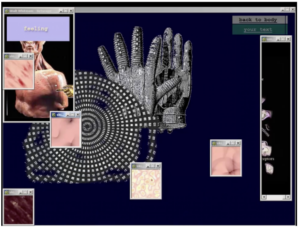

Expanded cinema in the 1980s and 1990s gave viewers a participatory role in cinema, allowing viewers to interact with the screen and change the narrative. Similarly, Internet artists of the 1990s created works with branching narratives in which viewers had the agency to choose the way they interact with a piece. Many artists used the interface of the internet to allude to the body’s interface, skin; Mariela Yeregui’s 1998 work, Epithelia, for instance, uses the internet as a material to explore the concept of the body and constructs a network of references to bodies that users explore through text, pictures, videos, and hyperlinks.

Mariela Yeregui, Epithelia, 1999, netart, image retrieved from Brian Mackern’s video navigation, https://vimeo.com/231800139.

In the 21st century, digital art continues to grow, yet challenges present themselves when preserving works of digital media, such as documentation efforts and the migration of hardware and software into newer platforms. It can also be difficult to establish the authenticity of a digital work, yet non-fungible tokens present digital artists with a sales mechanism that offers a trackable lineage of ownership (though it remains important to consider the material consequences of blockchain technologies and to engage with energy efficient processes of data verification). Like early cybernetic artists, digital artists continue to recontextualize new technologies. Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s 2019 work Remote Pulse, for instance, uses biometric technologies used for surveillance to enable a work that allows a user on each side of the U.S./Mexico border to feel each other’s heartbeat.

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Remote Pulse, 2019, Corian slab, aluminum mount, heart rate sensor plates, circuits, transducers, lightbulbs, image retrieved from the artist’s website https://www.lozano-hemmer.com/remote_pulse.php.

In line with the legacy of cybernetics, the final form of digital art is often unpredictable, and, in some cases, as seen in Cohen’s AARON or Lozano-Hemmer’s Remote Pulse, achieving a definitive final form is not the goal. However, this unpredictability is not unique to digital art alone; it is a characteristic shared by art across various media. Computer Nude echoes the aesthetics of pointillism paintings that continuously evolve based on the viewer’s position. Further, works from centuries ago are not exactly as they were originally, as painting pigments change over time and materials wear down. Digital media provides a unique opportunity for artists and viewers to actively participate in shaping an artwork’s evolution.

Sophie Cianfarani is a recent graduate of Cornell University, earning a degree in the History of Art. She joins Appraisal Bureau as an Appraisal Intern with previous experience working for curatorial and art advisory firms, as well as Cornell’s Mui Ho Fine Arts Library.